Traditional Water Management Systems of India

- By

- Gitanjali Maggo

- May-25-2025

Long before modern engineering solutions, India developed sophisticated water management systems that have sustained communities for centuries. These traditional systems, born from deep ecological understanding and community wisdom, represent some of the most ingenious water conservation techniques in human history. As we face growing water challenges, these ancient solutions offer valuable insights that can complement modern technologies.

The Rich Heritage of Water Wisdom

India's diverse geography and climate have necessitated region-specific water management approaches. From the arid deserts of Rajasthan to the flood plains of Bengal, communities developed unique systems adapted to local conditions. These systems share common principles: they work with natural water cycles, rely on community management, and integrate water conservation into cultural practices.

What makes these traditional systems remarkable is not just their technical ingenuity but their social sustainability. Most were managed through sophisticated community governance systems that ensured equitable access and responsible maintenance across generations.

Stepwells: Architectural Marvels for Water Access

Perhaps the most visually striking of India's traditional water structures are stepwells (known variously as vav, baoli, or bawdi). These structures, which combine water access with stunning architecture, feature a series of steps leading down to the water table. As water levels fluctuate seasonally, different levels of steps provide access.

The most elaborate stepwells, such as Rani ki Vav in Gujarat (a UNESCO World Heritage site) and Chand Baori in Rajasthan, feature intricate carvings and multiple levels of pavilions. Beyond their practical function, they served as community gathering spaces, places of worship, and respite from summer heat.

Key features of stepwells include:

- Temperature regulation: The deep, stone-lined chambers naturally maintain cool temperatures, reducing evaporation and providing relief during hot seasons.

- Groundwater access: By reaching down to the water table, stepwells provided reliable water access even during dry periods.

- Filtration: The stepped design allowed sediment to settle at different levels, naturally filtering water.

- Social spaces: Many stepwells incorporated gathering areas, making water collection a community activity rather than a chore.

Tank Systems: Community-Managed Water Storage

Across southern India, particularly in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, elaborate tank (or eri) systems have been the backbone of water management for over 1,500 years. These interconnected networks of human-made water bodies capture and store monsoon rainfall for year-round use.

The tank system of Tamil Nadu represents one of history's most sophisticated water management networks. At its peak, it included over 39,000 tanks connected through channels that followed natural topography. This system not only provided irrigation water but also recharged groundwater, prevented flooding, and created diverse ecosystems.

The governance of these tanks was equally impressive. Each tank was managed by a community council that determined water allocation, maintained infrastructure, and resolved disputes. This ensured equitable distribution and sustainable use across generations.

"The traditional tank system represents not just engineering knowledge but a profound understanding of ecology, hydrology, and community governance. Its principles remain relevant today."

— Dr. Anupama Mohan, Hydrologist

Kunds and Kundis: Desert Water Harvesting

In the arid regions of western Rajasthan, where annual rainfall might be as little as 100mm, communities developed remarkably efficient rainwater harvesting structures called kunds or kundis. These dome-shaped structures collect rainwater from a carefully prepared catchment area and store it underground, protected from evaporation and contamination.

A typical kund consists of:

- A circular catchment area sloping toward the center

- A central storage chamber, often lined with lime and ash for waterproofing

- A dome-shaped cover to prevent evaporation and contamination

- A small opening for drawing water

These structures can store water for months, providing drinking water through the dry season. The design minimizes evaporation losses, which can exceed 80% in open storage in desert regions.

Ahar-Pyne: Flood Water Management

In Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh, the ahar-pyne system managed the region's flood-prone rivers. This system consists of ahars (catchment basins) connected by pynes (channels) that divert river water during monsoons.

The genius of this system lies in its ability to transform flood risk into agricultural opportunity. During monsoons, excess river water is channeled through pynes into ahars, where it deposits nutrient-rich silt. As water levels recede, this enriched land becomes ideal for winter crops. The system simultaneously provides flood protection, irrigation, and soil enrichment.

Zabo: Integrated Water-Forest-Farm Management

In Nagaland, the Zabo (meaning "impounding water") system represents one of the most holistic approaches to water management. This indigenous system integrates forestry, animal husbandry, and agriculture with water conservation.

A typical Zabo system includes:

- Protected forests on hilltops that act as catchment areas

- Ponds at different elevations that collect runoff

- Channels that direct water through cattle yards, collecting nutrient-rich waste

- Terraced fields that receive this enriched water

This system demonstrates profound ecological understanding, creating a closed-loop system where water, nutrients, and energy flow efficiently through the landscape.

Challenges and Revival Efforts

Despite their sustainability and effectiveness, many traditional water systems fell into disuse during the colonial period and after independence. Several factors contributed to their decline:

- Centralization of water management under government control

- Emphasis on large-scale infrastructure like dams and canals

- Disruption of traditional community governance systems

- Changing land use patterns and urbanization

- Loss of traditional knowledge across generations

However, recent decades have seen growing interest in reviving these systems. Organizations like the Tarun Bharat Sangh in Rajasthan have helped communities restore thousands of traditional water harvesting structures, dramatically improving water security and agricultural productivity.

Government initiatives like the Jal Shakti Abhiyan now explicitly recognize the value of traditional water wisdom. Several states have launched programs to document, restore, and integrate traditional systems into modern water management frameworks.

Integrating Traditional Wisdom with Modern Technology

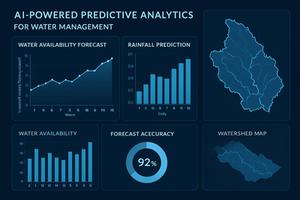

The most promising approaches don't treat traditional systems as museum pieces but as living technologies that can evolve and integrate with modern solutions. Artificial intelligence and remote sensing can enhance traditional systems in several ways:

- Optimizing placement: GIS and hydrological modeling can identify optimal locations for traditional structures like check dams and recharge wells.

- Monitoring performance: Sensor networks can track water levels, quality, and flow in traditional systems, providing data for better management.

- Predicting maintenance needs: AI algorithms can analyze structural and hydrological data to predict when maintenance is needed.

- Improving governance: Digital platforms can support community water governance, making traditional management systems more transparent and inclusive.

Projects like the stepwell restoration in Jodhpur demonstrate this integration. Here, traditional structures have been restored using modern materials and equipped with monitoring systems, while community management has been revitalized through digital platforms that track water use and maintenance responsibilities.

Conclusion: Learning from the Past, Building for the Future

India's traditional water systems represent not just historical artifacts but living examples of sustainable water management. Their principles—working with natural cycles, emphasizing community governance, and integrating water management into broader ecological and social systems—remain profoundly relevant today.

As we face growing water challenges exacerbated by climate change, population growth, and urbanization, these traditional systems offer valuable lessons. By combining their wisdom with modern technology and science, we can develop water solutions that are both innovative and grounded in centuries of proven practice.

The revival of traditional water systems represents not a step backward but a step toward a more resilient, sustainable, and equitable water future—one that honors the ingenuity of our ancestors while embracing the possibilities of modern innovation.